Stevie's Dad

- Claire Jordan

- Mar 10, 2023

- 4 min read

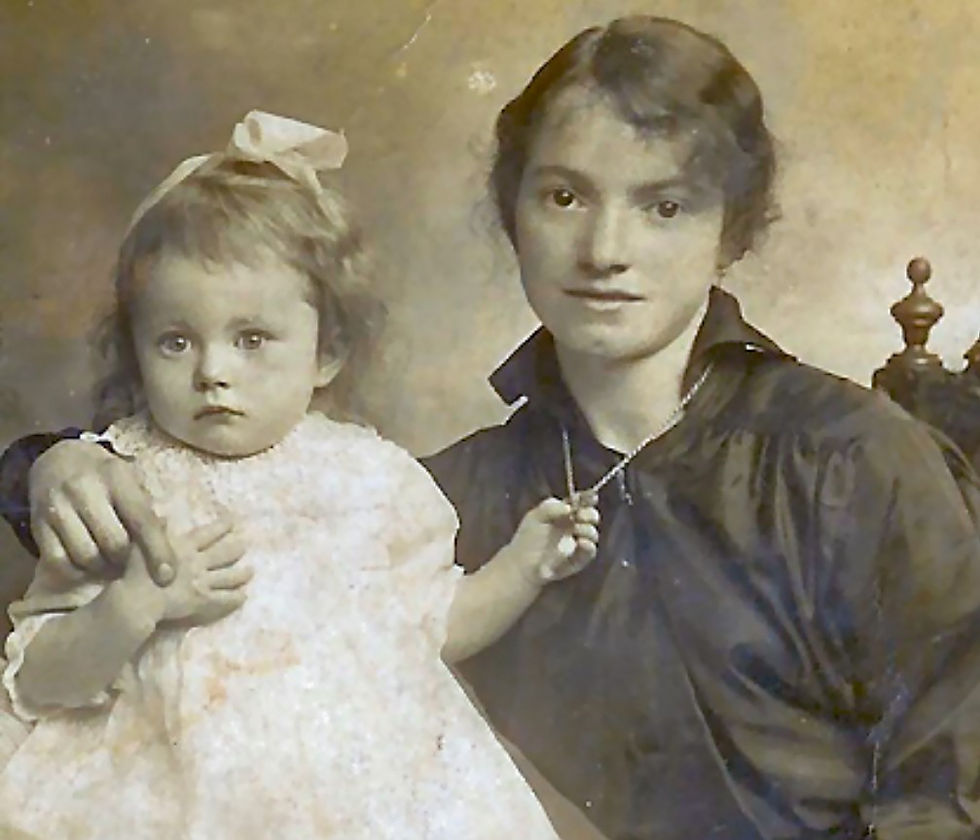

This is a story about a father who loved his only son more than life; I have no pictures of them to post with their story, so I thought maybe I’d offer up one of me with my own Dad; if this tale had been ours, I think he would try to find me too.

So little Stephen was born to newly married Joe and Sarah Morris at the end of 1898; Joe had a good job as an insurance agent’s clerk. Joe’s own parents lived with them in a cosy two-up, two-down on Rose Street in Ince-in-Makerfield, Wigan, for the first few years of the marriage and helped look after baby Stevie.

Joe’s Dad was a coal miner but Joe himself must have yearned for a different life for himself and his family and worked hard to make a success of his office job. Two little girls, sisters Bertha and Edna for big brother Stevie, followed on. Joe was doing well, keeping everything going and everyone together.

When the War came, Stevie was not yet 16 years old and as (officially at least), no one could be sent overseas to fight until they reached the age of 19, perhaps Joe and Sarah felt their son might be safe.

But the War ground on and by the beginning of 1918, conscientious Stevie stepped up and went to War, doing well and swiftly promoted to Lance Corporal.

Back home in Wigan, Joe and Sarah with the younger girls surely felt equal parts fearful for him and oh-so-proud.

By March 1918, the Germans were fast running out of resources and so launched one last all-out offensive to break the stalemate and strike a winning blow.

In many places, our positions were swamped, out-flanked, surrounded, overwhelmed. Much of the ground gained at such cost over the previous three years was lost.

Thousands of British and Commonwealth soldiers fell in as many minutes: lost in the chaos, wounded and taken prisoner only to die in enemy hands, perhaps buried by the enemy and the graves then lost.

On 11th April, the German Kaiserschlacht (the Kaiser’s Battle) had been sweeping all before it, despite heroic pockets of resistance, for more than two weeks and Stevie with his 2nd South Wales Borderers were holding the line at Steenwerck, just west of Armentieres.

They knew what was happening; they knew what was coming.

At dawn that day, the storm broke over them. After a trench mortar barrage, in the growing light the enemy attacked along a massive two-Division front, both Divisions falling back. The enemy outflanked them and attacked again from behind their positions.

Repeatedly, the Officers of Stevie’s 2nd Battalion collected and reorganised their dwindling numbers of men.

“Captain Bennett,” says the war diary, “commanding C Company on the left of the front line, formed a defensive flank but the distance was too great and the country enclosed.

About an hour or hour and a half later, the enemy again attacked and worked through the exposed flank. Battalion HQ was taken in flank and rear. Major Somerville was last seen with 1 Platoon of A Company defending a small portion of trench, but the enemy were close and rounded the flank.

Casualties were very heavy and men became disorganised, small parties fighting with different units for the remainder of the day.”

At daybreak that morning, the Battalion had been just under a thousand men strong.

By dusk, there were 140 men and three Officers left standing.

Stevie was not one of them.

Back home, Joe and Sarah would receive a telegram telling them that their son was officially Missing as of 11th April.

By the start of August, with no word received from or about Stevie, Joe wrote to the Red Cross and requested that their Wounded & Missing Enquiries Department look specifically for him. They would check lists received from the Germans about those taken prisoner, and his name would go out on the lists carried by Searchers, those wonderful men and women – volunteers – who toured medical facilities as close to the front as they were permitted, asking wounded men of the same Regiments if they had seen what had happened to those boys about whom specific enquiries had been made.

On 30th August, a reply was sent back to Joe in the negative. No one had seen or heard of the fate of his boy.

Was he wounded, in enemy hands, all forms of identification shot away, unable to communicate his name? The horrendous possibilities seemed endless. Was there any chance he was still alive? Or was all this desperate waiting and hoping and refusing to admit the possibility of the worst actually all in vain?

The last agonising hundred days of the War passed in an agony of suspense; still no word came.

Finally the Armistice, 11th November. Surely now, they’d hear, one way or another. Surely now.

Joe gave it a week and then wrote once again to the Red Cross on 18th, renewing the request for them to look for his boy.

When the reply came on 19th November, it was perhaps worse than a blank No.

The Red Cross’s telegram to Joe let him know that on 24th August, Stevie’s paybook had been recovered by the Germans, collected from an unnamed prisoner at a POW camp. They had no further information on what that meant in terms of Stevie’s whereabouts or condition. As the Germans put it: death was questioned.

So Joe and Sarah’s awful wait continued until one day in the summer of 1920, No.30 Graves Registration Unit (responsible for clearing the battlefields in the Steenwerck sector where Stevie’s Battalion had fought and died that spring day two years before) found a pocket of South Wales Borderers in a field.

Whether they’d simply lain all this time where they’d fallen or been buried by the conquering enemy is unknown but no grave markers were in evidence.

Identified by the metal ID disc given to him by his Dad, Stevie would turn out to be one of these precious few.

He was reburied in the nearby CWGC cemetery at Croix-du-Bac in October 1920. Joe and Sarah, Bertha and Edna at home at least now had an answer.

It is an awfully sad tale, I know, but it glows fiercely with love, even after all these years, and must not be forgotten.

Comments